BAZARLOADER: Unpacking an ISO File Infection

BAZARLOADER (aka BAZARBACKDOOR) is a Windows-based loader that spreads through attachments in phishing emails. During an infection, the final loader payload typically downloads and executes a Cobalt Strike beacon to provide remote access for the threat actors, which, in a lot of cases, leads to ransomware being deployed to the victim’s machine.

In this initial post, we will unpack the different stages of a BAZARLOADER infection that comes in the form of an optical disk image (ISO) file. We will also dive into the obfuscation methods used by the main BAZARLOADER payload.

To follow along, you can grab the sample as well as the PCAP files for it on Malware-Traffic-Analysis.net.

SHA256: 0900b4eb02bdcaefd21df169d21794c8c70bfbc68b2f0612861fcabc82f28149

Step 1: Mounting ISO File & Extracting Stage 1 Executable

Recent BAZARLOADER samples arrive in emails containing OneDrive links to download an ISO file to avoid detection since most AVs tend to ignore this particular file type. With Windows 7 and above integrating the mounting functionality into Windows Explorer, we can mount any ISO file as a virtual drive by double-clicking on it.

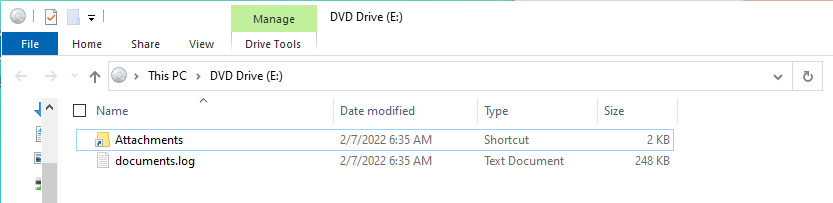

When we mount the malicious ISO file, we see that a drive is mounted on the system that contains a shortcut file named “Attachments.lnk” and a hidden file named “documents.log”.

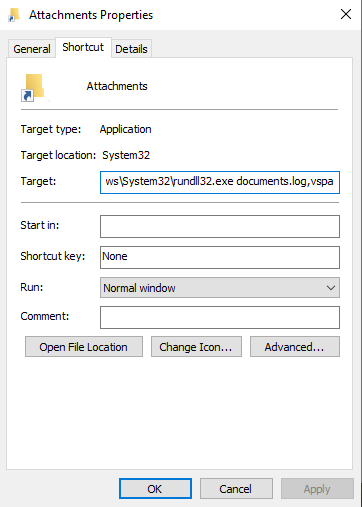

The shortcut file has to be run by the victim to begin the chain of infection. We can quickly extract the actual command being executed by this shortcut from its Properties window.

C:\Windows\System32\rundll32.exe documents.log,vspa

Once the victim double-clicks on the shortcut file, the command executes the Windows rundll32.exe program to launch the “documents.log” file. This lets us know that the file being launched is a DLL file, and the entry point is its export function vspa.

Step 2: Extracting Second Stage Shellcode

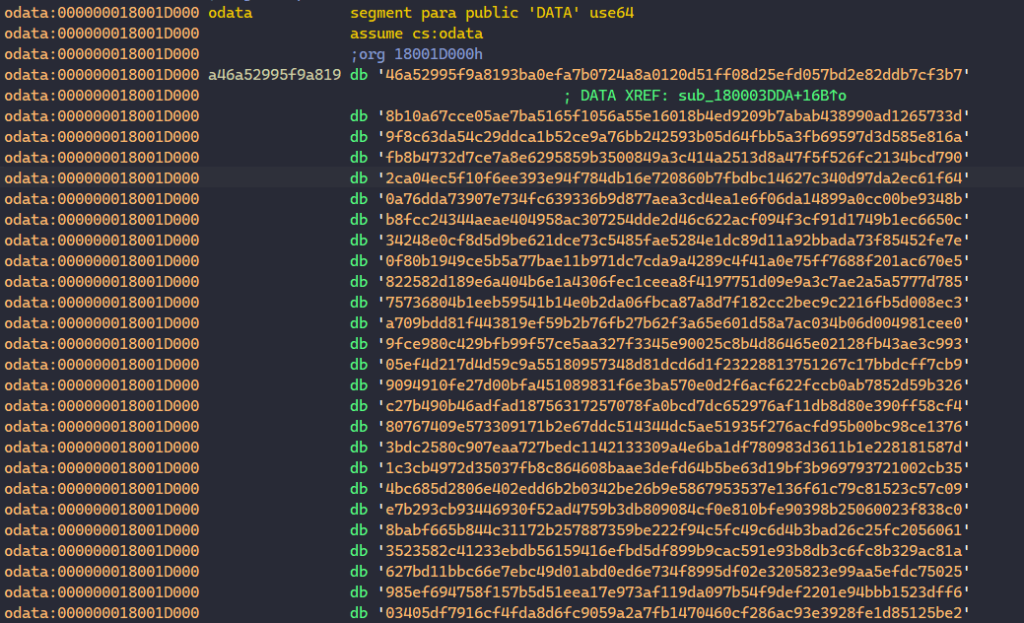

Taking a quick look in IDA, we can somewhat tell that the extracted DLL is packed since it has only a few functions and a really suspicious looking buffer of ASCII characters in its custom .odata section.

With that in mind, we will just perform some quick static analysis to determine where we can dump the next stage.

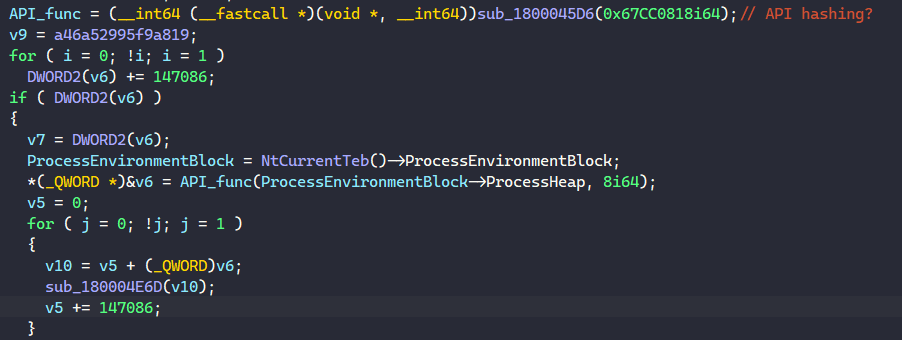

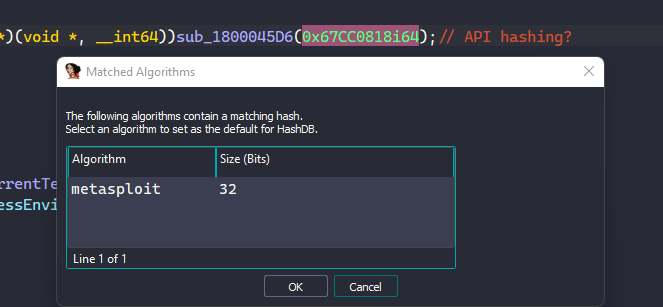

In the first function of the vspa export, we see sub_1800045D6 takes a DWORD in as the parameter. This function returns a variable that contains an address to a function that is later called in the code.

At this point, we can safely guess that sub_1800045D6 is an API resolving function, and the parameter it takes is the hash of the API’s name. Because this is still the unpacking phase, we won’t dive too deep into analyzing this function.

Instead, I’ll just use OALabs’s HashDB IDA plugin to quickly reverse-lookup the hashing algorithm used from the hash. The result shows that the hash corresponds to an API name hashed with Metasploit’s hashing algorithm ROR13.

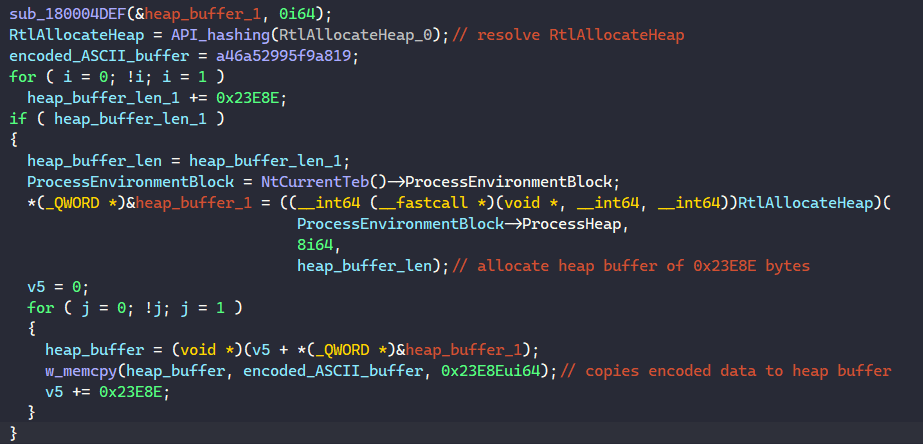

After determining the hashing algorithm, we can use HashDB to quickly look up the APIs being resolved by this function. It becomes clear that this function resolves the RtlAllocateHeap API, calls that to allocate a heap buffer and writes the encoded ASCII data to it.

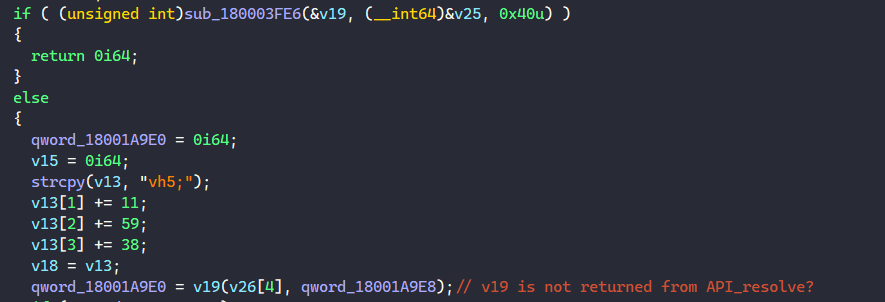

From this point onward, we can guess that the packer will decode this buffer and launch it somewhere later in the code. If we skip toward the end of the vspa export, we see a call instruction on a variable that is not returned from the API resolving function, so it can potentially be our tail jump.

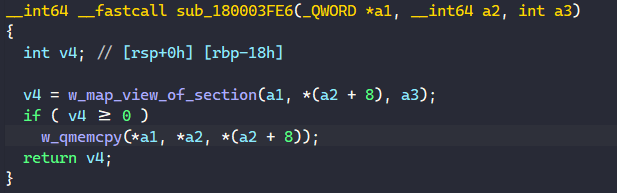

The last function to modify that v19 variable is sub_180003FE6, so we can quickly take a look at that.

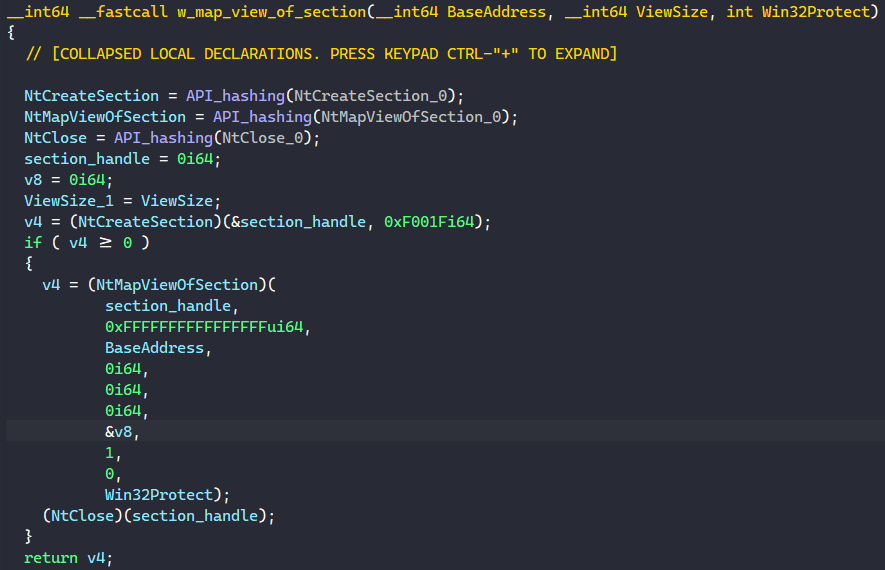

It turns out the sub_180003FE6 function just resolves and calls NtMapViewOfSection to map a view of a section into the virtual address space and writes the base address of the view into the v19 variable. Then, it just executes qmemcpy to copy the data in the second variable to the returned virtual base address.

This tells us two things. First, our guess that the v19 variable will contain the address to executable code is correct. Second, we know that the executable code is shellcode since the data is mapped and executed directly at offset 0 from where it is written.

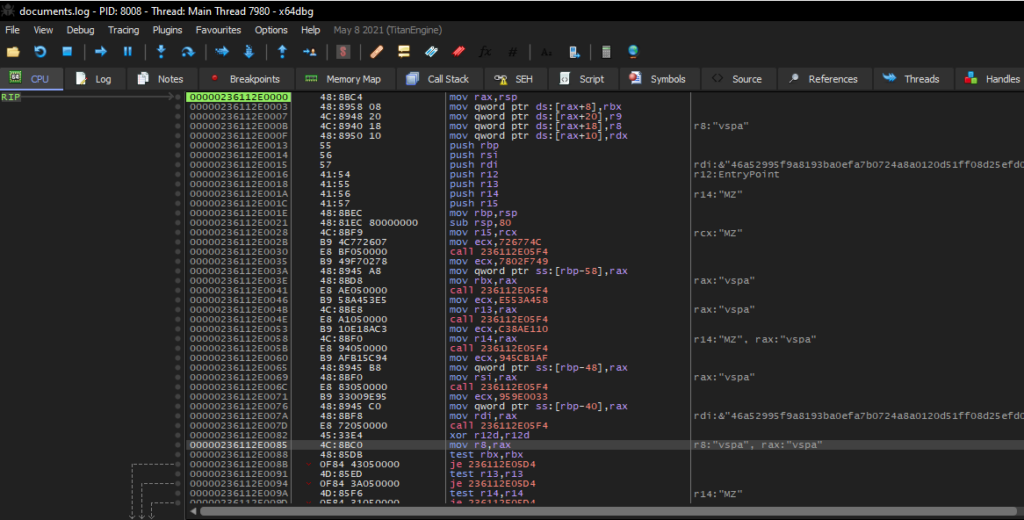

From here, we can set up x64dbg, execute the DLL file at the vspa export, and break at the call instruction. After stepping into the function, we will be at the head of the shellcode.

We can now dump this virtual memory buffer to retrieve the second stage shellcode for the next unpacking step.

Step 3: Extracting The Final BAZARLOADER Payload

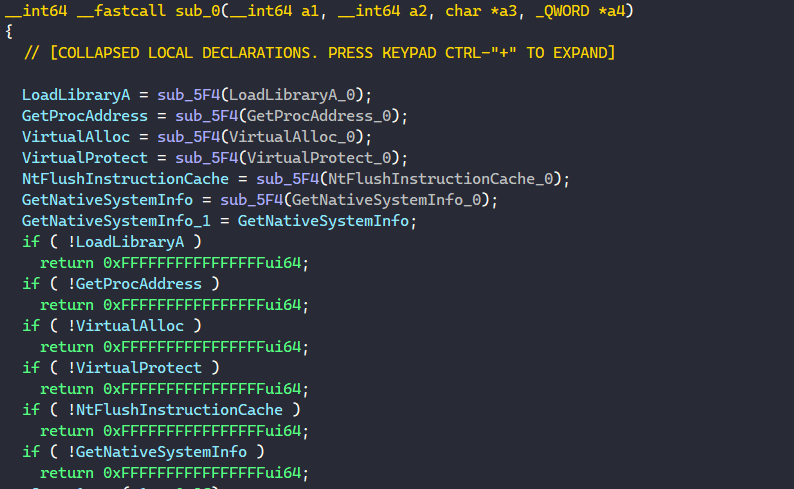

When we examine the shellcode in IDA, we can quickly use the same trick with HashDB above to see that the shellcode also performs API hashing with Metasploit’s ROR13.

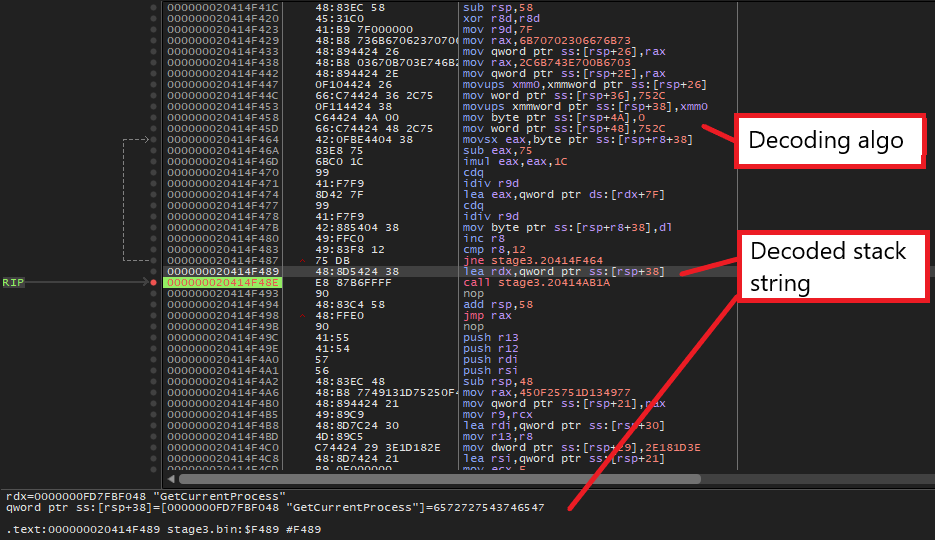

At the entry point above, the shellcode resolves a set of functions that it will call, most notably VirtualAlloc and VirtualProtect. These two functions are typically used by packers to allocate virtual memory to decode and write the next stage executable in before launching it.

With this in mind, our next step should be debugging the shellcode and setting breakpoints at these two API calls. We can pick up where we are after dumping in x64dbg during Step 2, or we can launch the shellcode directly in our debugger using OALabs’s BlobRunner or similar shellcode launcher.

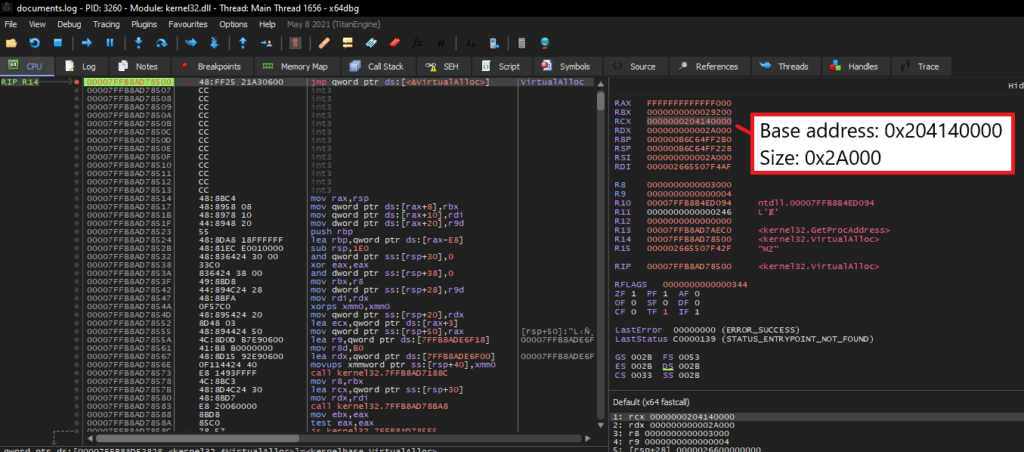

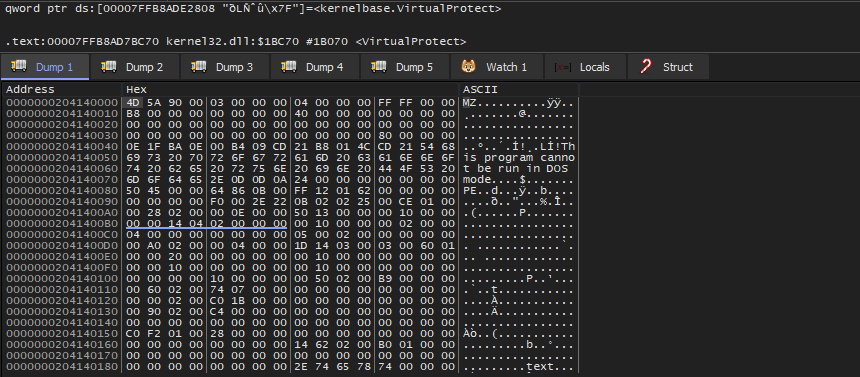

Our first hit with VirtualAlloc is a call to allocate a virtual memory buffer at virtual address 0x204140000 with the size of 0x2A000 bytes.

We can run until VirtualAlloc returns and start monitoring the memory at address 0x204140000. After running until the next VirtualProtect call, we see that a valid PE executable has been written to this memory region.

Finally, we can dump this memory region into a file to extract the BAZARLOADER payload.

Step 4: BAZARLOADER’s String Obfuscation

As we begin performing static analysis on BAZARLOADER, it is crucial that we identify obfuscation methods that the malware uses.

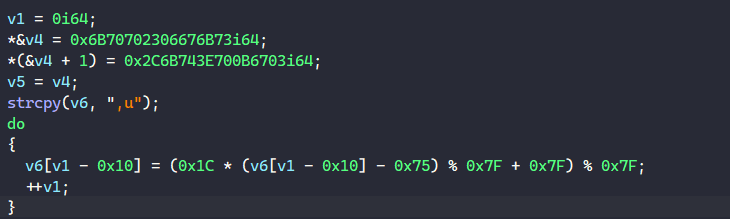

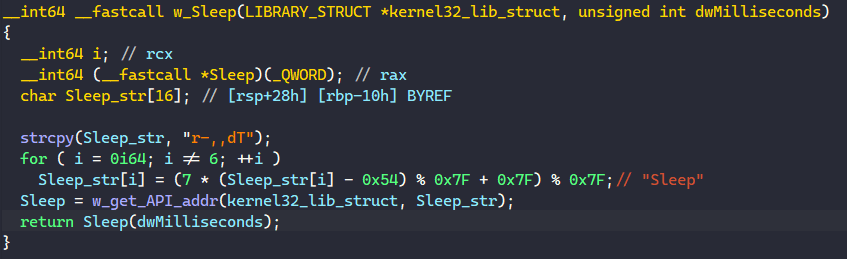

One of those methods is string obfuscation, where the malware uses encoded stack strings to hide them from static analysis.

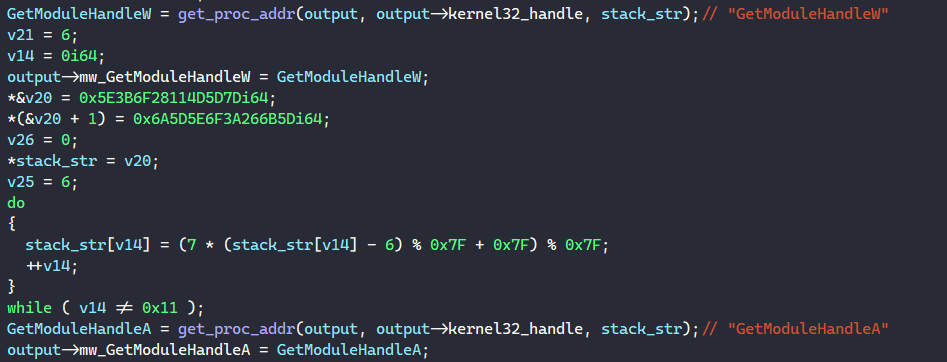

As shown, a typical encoded string is pushed on the stack and decoded dynamically using some multiplication, subtraction, and modulus operations.

There are different ways to resolve these stack strings, such as writing IDAPython scripts, emulation, or just running the program in a debugger and dumping the stack strings when they are resolved.

Step 5: BAZARLOADER’s API Obfuscation

BAZARLOADER obfuscates most of its API calls through a few structures that it constructs in the DllEntryPoint function.

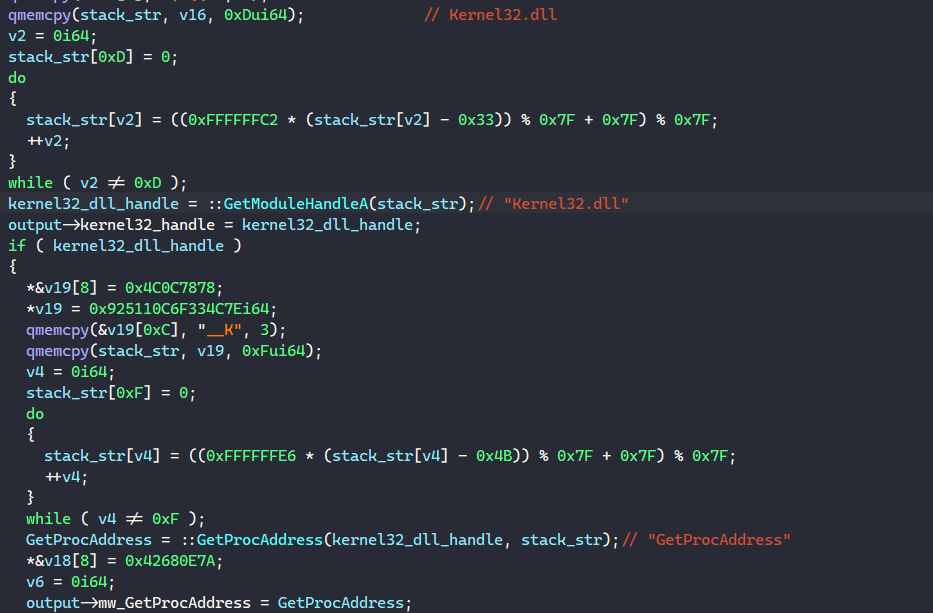

First, the malware populates the following structure that contains a handle to Kernel32.dll and addresses to API required to load libraries and get their API addresses.

struct API_IMPORT_STRUCT {

HANDLE kernel32_handle;

FARPROC mw_GetProcAddress;

FARPROC mw_LoadLibraryW;

FARPROC mw_LoadLibraryA;

FARPROC mw_LoadLibraryA2;

FARPROC mw_FreeLibrary;

FARPROC mw_GetModuleHandleW;

FARPROC mw_GetModuleHandleA;

};

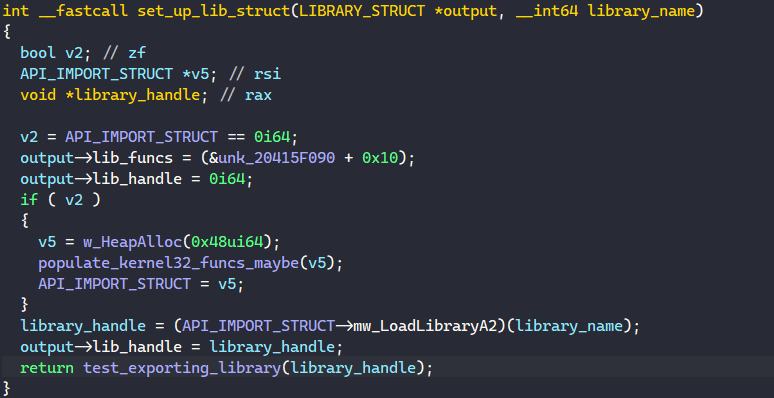

It calls GetModuleHandle to retrieve the handle to Kernel32.dll, calls GetProcAddress to retrieve the address of the GetProcAddress API, and writes those in the structure.

Using the structure’s GetProcAddress API field, BAZARLOADER retrieves the rest of the required APIs to populate other fields in the structure. This API_IMPORT_STRUCT structure will later be used to import other libraries’ APIs.

Next, for each library to be imported, BAZARLOADER populates the following LIBRARY_STRUCT structure that contains a set of functions to interact with the library and the library handle.

struct LIB_FUNCS

{

FARPROC free_lib;

FARPROC w_free_lib;

__int64 (__fastcall *get_API_addr)(API_IMPORT_STRUCT*, HANDLE, char*);

};

struct LIBRARY_STRUCT

{

LIB_FUNCS *lib_funcs;

HANDLE lib_handle;

};

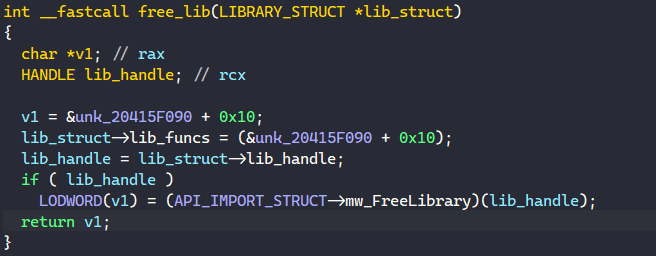

The first 2 functions in the LIB_FUNCS structure just call the FreeLibrary API from the global API_IMPORT_STRUCT to free the library module.

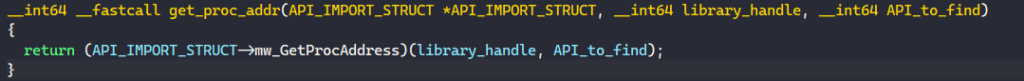

The third function calls the GetProcAddress from the API_IMPORT_STRUCT’s field to retrieve the address of an API exported from that specific library.

To begin populating each LIBRARY_STRUCT structure, BAZARLOADER decodes the library name from a stack string and populates it with the corresponding set of functions and the library handle retrieved from calling LoadLibraryA.

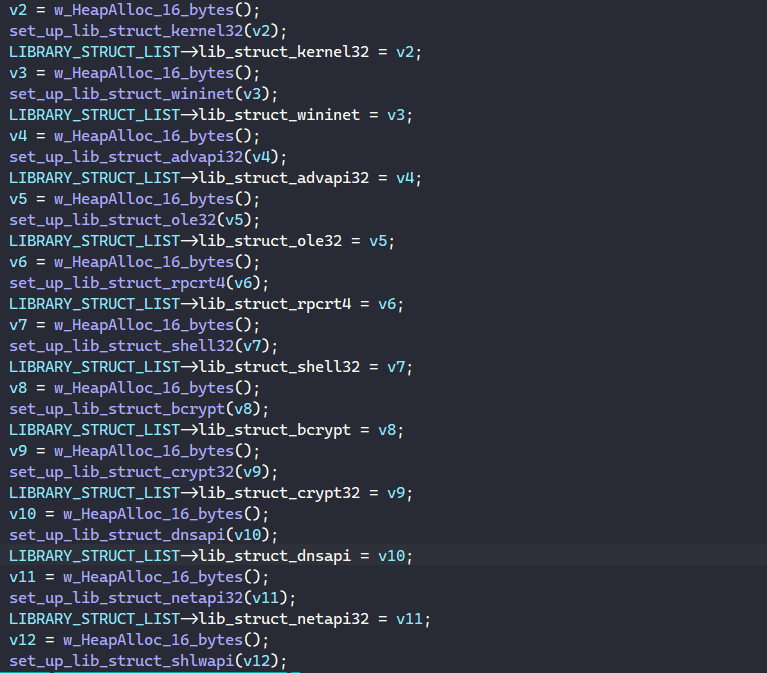

Below is the list of all libraries used by the malware.

kernel32.dll, wininet.dll, advapi32.dll, ole32.dll, rpcrt4.dll, shell32.dll, bcrypt.dll, crypt32.dll, dnsapi.dll, netapi32.dll, shlwapi.dll, user32.dll, ktmw32.dllThe LIBRARY_STRUCT structures corresponding to these are pushed into a global list in the order below.

struct LIBRARY_STRUCT_LIST

{

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_kernel32;

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_wininet;

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_advapi32;

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_ole32;

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_rpcrt4;

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_shell32;

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_bcrypt;

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_crypt32;

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_dnsapi;

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_netapi32;

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_shlwapi;

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_user32;

LIBRARY_STRUCT *lib_struct_ktmw32;

};

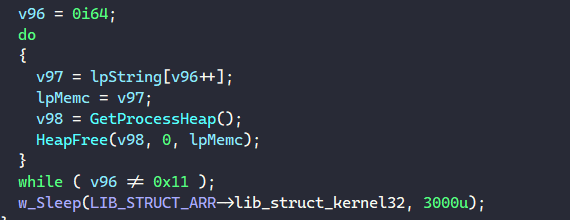

After this global list of LIBRARY_STRUCT is populated, an API can be called from a function taking in its corresponding library’s LIBRARY_STRUCT structure and its parameters.

This function resolves the API name from a stack string, retrieves the API’s address using the get_API_addr function from the library structure, and calls the API with its parameters.

The way the wrapper function is setup to call the actual API is really intuitive, making the code simple to understand through static analysis. However, it’s a bit more difficult to automate the process since there is no API hashing involved.

For my analysis, I just manually decode the stack strings in my debugger and rename the wrapper function accordingly.

At this point, we have fully unpacked BAZARLOADER and understood how the malware obfuscates its strings and APIs to make analysis harder.

In the next blog post, we will fully analyze how the loader downloads and launches a Cobalt Strike beacon from its C2 servers!

Comment (1)

Comments are closed.

BAZARLOADER: Unpacking an ISO File Infection – 0ffset Training Solutions – Library 11: Antigonish Project Edition

20th April 2022[…] https://www.0ffset.net/reverse-engineering/bazarloader-iso-file-infection/ […]